Fine Art Giclée has been a passion of Spectrum Imaging since technology made the digital fine art reproduction possible. We have dedicated ourselves to the process through decades of experience with the most cutting edge scanners, printers, inks and medias.

Copyright © 2011 Spectrum Imaging

THE HISTORY OF GICLEE AND DIGITAL FINE ART PRINT MAKING

There are a number of accounts of how digital fine art print making came to be, with the most notable concerning the origins of the term coined to describe the process: giclée. With all the experience we gained from being on the bleeding edge of technology since 1992 we thought it would be more interesting to learn how we were a part of history in the making and not so much on who is credited with coining the term “giclée”. When we opened Spectrum Imaging in 1992, we were the first company in Monterey, California to offer print for pay color printing services using a Tektronix Phaser III printer. Ink jet printing was in its infancy and there just weren’t very many ink jet receptive papers available. The Phaser III was unique because it sprayed melted wax onto the paper and gave very consistent results and was one of 3 or 4 printers of the era that were Pantone certified. Other color printing options were dye-sublimation onto special coated papers or electrostatic (e-stat) plotters. While the dye-sublimation prints looked near continuous tone, where printed dots are nearly imperceptible, its lack of paper choices and extremely low uv stability made it useful as a photographer’s proof print, at best. E-stat on the other hand, while uv stable for a couple of years, was an extremely low resolution, grainy print.

Iris Graphics develops a textile and prepress proofer

In 1989, Iris Graphics, a subsidiary of prepress giant, Scitex, had introduced the Iris printer. The Iris was developed for prepress and textile proofing using a sophisticated 4 color ink delivery system that could print on virtually any type of untreated substrate, including canvases and the very popular Arches watercolor papers. The paper or fabric was taped to a metal drum and spun at up to 200rpm. A printhead, mounted on a screw drive, would move down the length of the drum and each of its four inkjet nozzles would continuously fire ink at the drum through a small corridor called the deflection structure. Here is where the Iris’ engineering was amazing; each of the Iris’ key elements were electrically charged. A quartz crystal created the frequency in which drops of ink were sized and fired toward the drum. The drum was positively charged and pulled the negatively charged ink droplet towards it through the deflection structure at 90mph. This continuous ink delivery system would then send a current through the deflection structure to bend the ink droplets into a collection system when an ink droplet was not required at that location on the print. The ink delivery system was 300dpi which is low by today’s modern standards, but the nozzle could create 32 different drop sizes at any given position on the print with the smallest drop size the size of a red blood cell, which gave the Iris an apparent resolution of 1,800dpi. Rather than use a random dot structure, the Iris had a very distinguishable rosette pattern similar to an offset printing press.

Getting serious about digital fine art printing

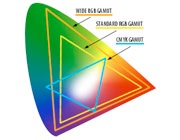

While the Iris could create an unquestionably magnificent print, there were many challenges. First, the cost to get in the game. Iris printers were very expensive. The smallest printer, the 10.6x17.2inch (not quite 11) Iris 4012, cost us $30,000, while the largest 3047 cost $125,000. When we were in full Iris production in the mid to late 90’s, we operated a 4012, 5030, mid-sized 3024, a 3047 and a re-engineered iXia 3047; that’s over $250,000 in printers! The next challenge was staying in the game. Iris printers were notoriously expensive to maintain. Getting new parts meant getting expensive service contracts. So, recertified parts ruled the day, but those parts came with quirks. Since you could not see the results of a print until the drum had stopped spinning, you wouldn’t know that an errant ink drop had ruined your print, which sometimes took an hour to complete. The final hurdle was coaxing the best color out of your Iris. Since it was only a 4 color printer, creating custom Color Look Up Tables (CLUTs) was critical. CLUTs that transformed the color space you were working with in Photoshop to that of the Iris required a great deal of understanding the science of color. We had formed a friendship with Urban Digital Color’s founder Robert Buchenmier, who was the poster child for Scitex and Iris, appearing in their Iris fine art print ads. We had collaborated with Buchenmier on the production of the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Deadly Beauty exhibit, which was to become the largest digitally produced exhibit of that time. Buchenmier shared his experience working with a Disney Imagineer to create his custom CLUTs and we had shared our experience with Scitex’s Smart scanner which we each operated in our respective shops.

Its all about the ink

While the Iris is still considered a beautifully rendered print, with a quality and character that is still unrivaled in our opinion, it suffered from digital printmaking’s achilles heel: print permanence. Because the Iris was intended as a proofing device, the inks that were originally introduced with it were suitable for just that, proofing. The Graphics Arts (GA) ink set was developed for matching standard swop offset press inks and the Industrial Design (ID) ink set was developed for textile proofing, but was well suited for printing on canvas and watercolor papers. These are the inks that Nash Editions had also started with when the 3047 was first introduced. There was a rush to market with these new digital fine art prints without really understanding the uv stability of the inks. Galleries, museums and collectors invested in the prints early on, only to watch their brilliance fade away. Manufacturers scrambled to develop inks that were more stable, but they were hampered by the Iris’ aqueous based ink system and extremely small nozzle size. Longer lasting pigment inks were introduced by a number of manufacturers which had larger particles than the dye inks that the Iris preferred. Nozzles were clogging all across America. Eventually, companies like Lyson and Iris figured it out and we eventually settled on using Iris’ Equipoise inks that were developed specifically for fine art. It may have been too late, though; the Iris, along with digital print making in general, suffered a black eye in the fallout.

Epson enters the fine art market

In the mid to late 90’s, there was a tremendous amount of education and damage control that accompanied digital fine art reproductions. Irises that had prematurely faded left a bad taste in the mouths of Galleries all over the country. Artists and galleries went back to pushing C-prints and lithos because they were a known. The industry coined the term “giclée” to try to distance these new Iris prints based on more stable ink technologies from those failures of the past. Shops like ours had to educate artists, galleries and buyers how these new prints were different than those from the recent past by extolling the findings of Wilhelm Imaging Research. Wilhelm began collecting vast amounts of data regarding accelerated light fade testing on the ink systems and substrates of ink jet prints. So, while Iris shops around the country used any number of ink sets, Epson came along in 2000 with a drop on demand 720dpi printer that was a tenth of the cost of an Iris. Epson’s entry into high resolution, large format printing would change everything. For $5,000, you could purchase a Stylus Pro 9500, that used a 6 color pigment based ink, that was nearly as fast as an Iris and was technically, higher in resolution. In the year of its introduction, few artist quality, coated medias existed for the Epson printers, but for the Iris, the writing was on the wall.

The label “Giclée” emerges

The well established digital print makers using Iris printers and fine art ink sets began using the term “giclée” to describe their Iris prints. Some will argue who coined the term first and what the term means literally, though, few disagree that it was a fabricated French word to describe the ink jet process; “to spray forcefully” is the definition we chose to use. The term was created as a marketing ploy to elevate the image of the Iris print and distance new Iris prints from those failures of the past. Equally important, shops with substantial investment in Iris printers were seeing new entrants in the market that were using much cheaper printers and therefore misconstrued as inferior. So, Iris prints were sold under the badge, Iris Giclée, to differentiate themselves. Quickly, though, the term became as ubiquitous as “Kleenex” and was thrown around to describe every type of digital inkjet print, including those from Epson, ColorSpan and Roland. We chose to to differentiate the two very different products by calling them what they were, Iris Giclée and Epson Stylus Giclée, in an effort to be as transparent as possible with the artist and the print buyer.

High speed, UV stable prints are now possible.

Spectrum has always prided itself in working with the latest imaging technologies to get the most out of its devices. Years earlier, we had done some amazing things with our HP DesignJet 3000 and one of our first large format printers, the NovaJet Pro 50. Our distributor was so impressed at the reproductions we had achieved with the NovaJet’s limited color gamut, that they let us in on a little secret at Epson; Epson was about to revolutionize digital fine art with a new high speed 1440dpi printer with an ink set that would last 200 years! Epson and our distributor worked to get us the first Stylus Pro 10,000 west of the Mississippi to see what we could do with it. We would typically work with a new technology for a few months before we would bring it to market, and in October 2001, we began selling reproductions from our first non-Iris fine art printer. It was amazing; the Stylus Pro 10,000 was 3x’s faster than our iXia and you could take the prints right out of the printer and run them under water without damaging the print. Moisture had always been a challenge with the Iris, forcing us to coat most prints with an awful solvent sealant, and here we were able to dunk prints straight off of the new printer into a tub of water.

Epson overcomes its own hurdles bringing their brand of fine art to market

Epson’s first take on fine art printing had its own shortcomings. The Stylus Pro printers relied on a fixed drop size that the printer would use in a stochastic pattern, placing ink drops closer together for denser colors and farther apart for lighter colors. This method was effective, but the prints still didn’t look as sharp or have the same painterly feel of the Iris. The Stylus Pro 10,000’s Archival Ink set had terrible color gamut and suffered from metamerism, the effect where under different lighting conditions, color in the prints would change dramatically. The chemistry of the ink caused different light sources to reflect sometimes unpredictably, causing large shifts in color. From the daylight of our production environment, through the office to the proofing stations, and out to the lobby, the print could change 3 or 4 times. We were forced to limit the guarantee on our Stylus Pro prints to daylight viewing only, which was difficult because we couldn’t control how a print was going to be viewed by an audience. Realizing the large available market, Epson continued to develop better printers and introduce new ink sets along with each new series that ever increased color longevity and stability. In 2003, we moved to the Stylus Pro 9600, probably the most popular amongst fine art printers, in 2005, the Stylus Pro 9800 and in 2007, the Stylus Pro 11880. Epson had along the way licensed their printhead technology to Roland, Mutoh and Mimaki, who developed their own fine art printer offerings and eventually killed off the viability of continuing to offer Iris prints. In 2004, we sold our last Iris printer to a company in Texas that was forced to keep a stable of them to reproduce legacy prints.

Looking back on 25 years of fine art print making

Its easy to think that all you need to do is get an inexpensive printer and start hitting command-P, and for what its worth, with all the trials and tribulations that went on over that time with different printer, coating and ink technologies, printing really is the easiest part. Among the cliche’s that we enjoy a chuckle over but find to be truly self-evident is the saying “Garbage In - Garbage Out”. Those that have been serious about digital fine art print making have always pushed technology further, trying to wring as much out of it as possible in the hopes of satisfying their passion for the richest color, the most faithful reproductions or the most emotionally satisfying experience. Not nearly as trendy as the impasto embellished prints or the craquelure canvases of the past decade, has been the underlying need to manage color and to manage it well. Shops like ours saw the value proposition in high end color management and we invested in viewing rooms, densitometers, colorimeters, spectrophotometry, robotics, monitors, scanners and a digital photo studio so that we could honestly say, that we have the most faithful digital reproduction capabilities. So, while the future will likely include more and more print making going in-house, the art of faithfully reproducing artwork in print relies on faithfully capturing and digitizing artwork in the first place and controlling color throughout the print making workflow. It is sometimes a daunting task, but the satisfaction in seeing an amazing reproduction is where our passion lies and it drives us to always improve our processes.

Iris 3047 print underway:

The Iris printed onto a substrate that was taped to a drum, which spun at 200rpm. Ink was sprayed onto the substrate at 90mph!

The Iris 3047 and later the iXia created the digital fine art market.

Iris Equipoise fine art ink set, like the FA ink set from Lyson, made UV stable print making possible on the Iris series printers.

Spectrum was the first in the West to receive the Stylus Pro 10,000, Epson’s first high speed fine art quality printer.

The last of our 5 Iris printers is shipped off to Texas in 2004.

It marked the end of an era that saw the birth of digital fine art print making.

Color Look Up Tables map how colors move from one color space to another, like from a scanner to a monitor and then to a printer with a given resolution, ink and substrate.